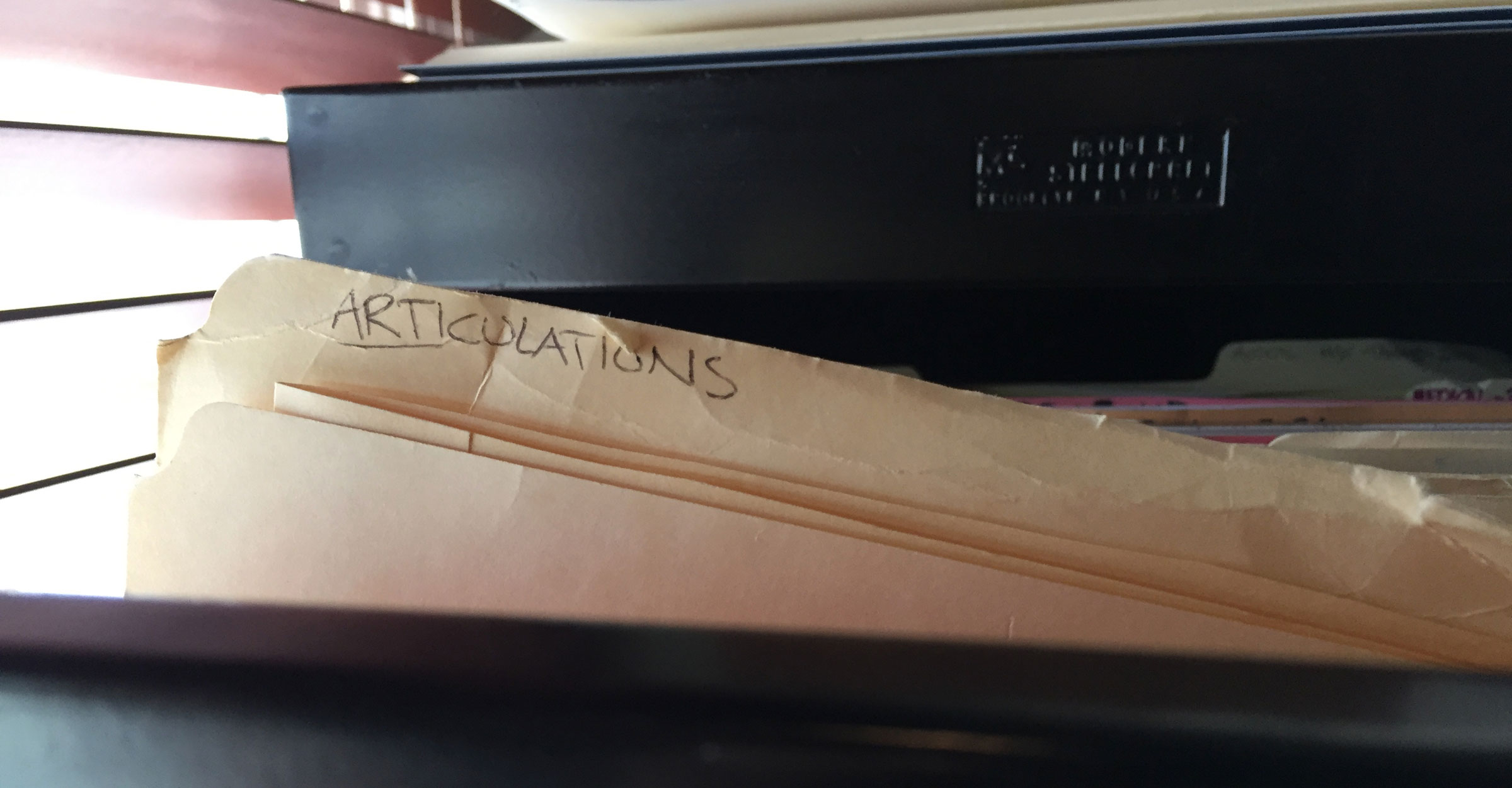

There is a folder in my filing cabinet that’s been there since 1980. It is old and worn, its tab bent and pulled so many times it threatens to fall off—or even more likely—dissolve away. It is of another time—another life. The handwriting on the folder’s tab is mine, but it is a different me: single, young, and living for the moment.

Yet, this younger me, who’s future was only the next day, had the presence of mind to find a single manila file folder and label it “Articulations.” The contents of this folder would forever be devoted to a friend of mine who had a singular, unparalleled mastery of the malaprop.

His name was Art Jeinnings. Not Arthur, or Artie.

Art.

And if you think that “Jeinnings” is pronounced with a long “i,” like “J-EYE-nings,” you would be wrong. I mean, right. I mean, it was pronounced “J-EYE-nings,” but Art got so tired of correcting people that pronounced it “Jennings,” that he gave up and went with the new pronunciation, unintentionally implementing a serious alteration to the history of the Jeinnings family. (Art told me that Ricky, his son, took it a step further after Ricky went out for the football team. They mistakenly spelled his name as “Jennings” on the back of his jersey, and Ricky went all in—embracing the new spelling as his own.)

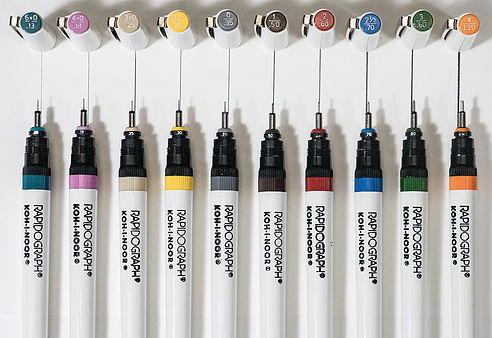

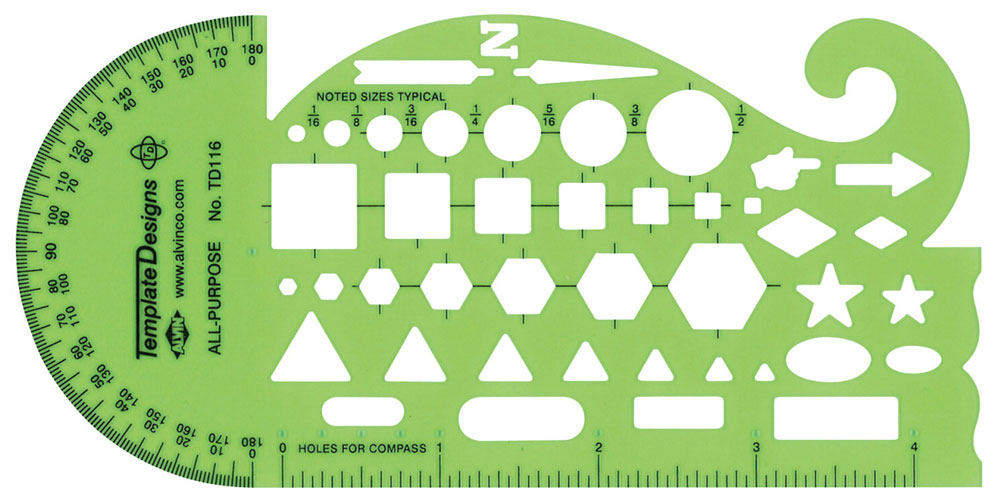

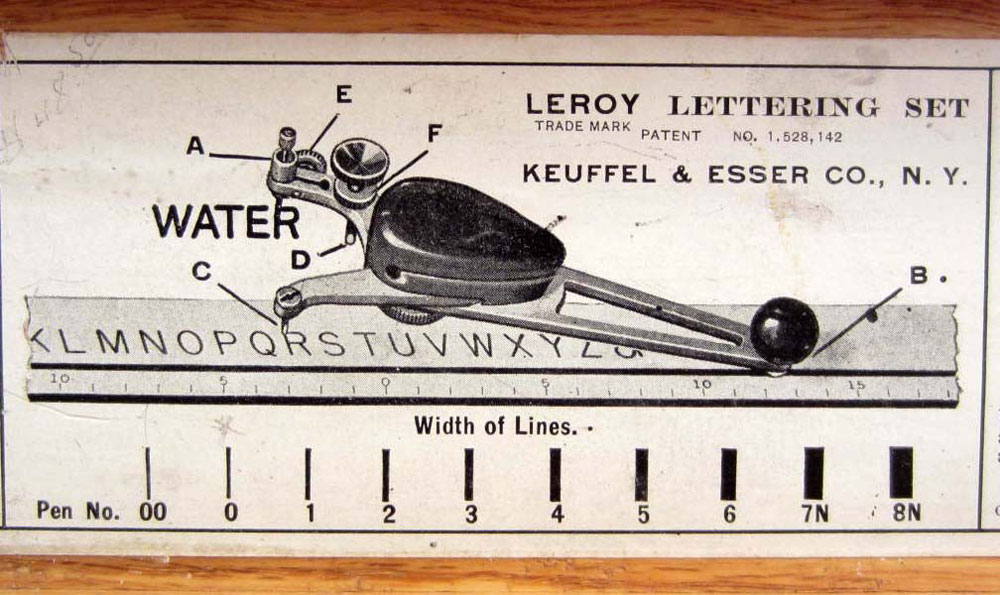

Art and I worked together at A.M. Cable & Communications, a company that mapped and designed cable television systems. I was as a draftsman. (Hey, it was 1980. The women there were draftsmen, too.) I drew roads and telephone pole locations on large maps. All by hand. No computers. Our tools were Koh-i-noor Rapidograph ink pens, plastic templates, and Leroy Lettering sets.

(I will not let myself go down the rabbit hole of the nostalgic brilliance of the Leroy Lettering system. Google it sometime. It’s hard to believe that’s how work got done.)

There were about ten draftspeople at A.M. Cable, and we were at the bottom of the job hierarchy chart. We’d lay heavy translucent mylar over large US Geological Survey maps, trace the roads in ink, make blueline copies of our work, and then send them out into the field where telephone pole locations would be plotted and mapped by the much-better-paid field guys. Then they’d return the marked-up maps to us, and we’d get out our trusty Leroy Lettering sets and neatly transpose their information on the original mylar.

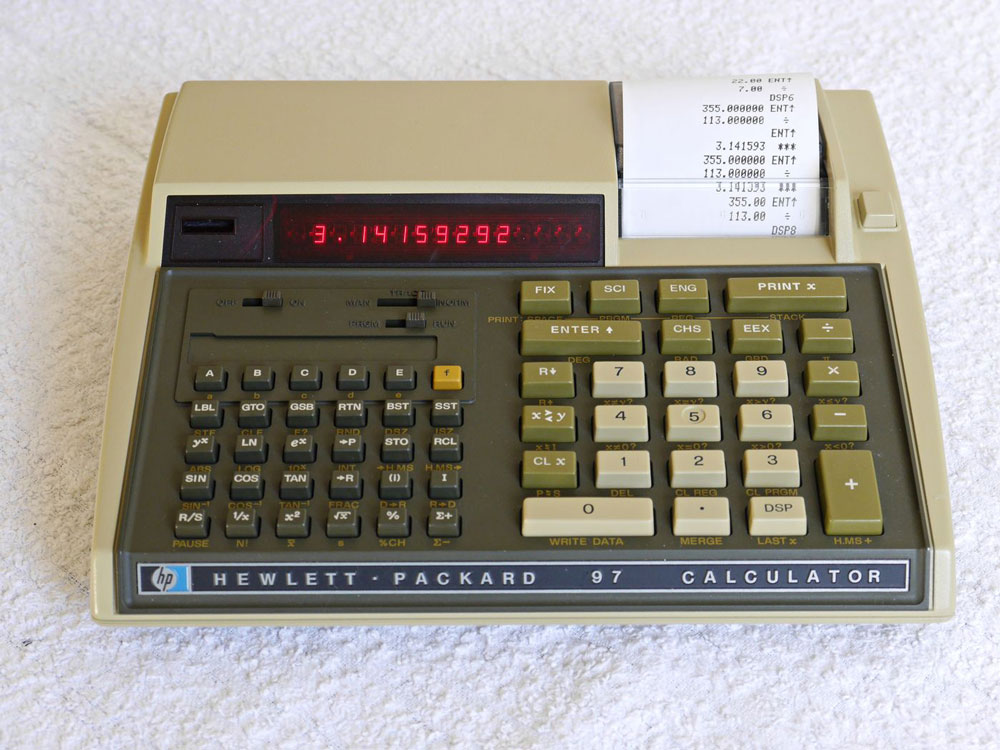

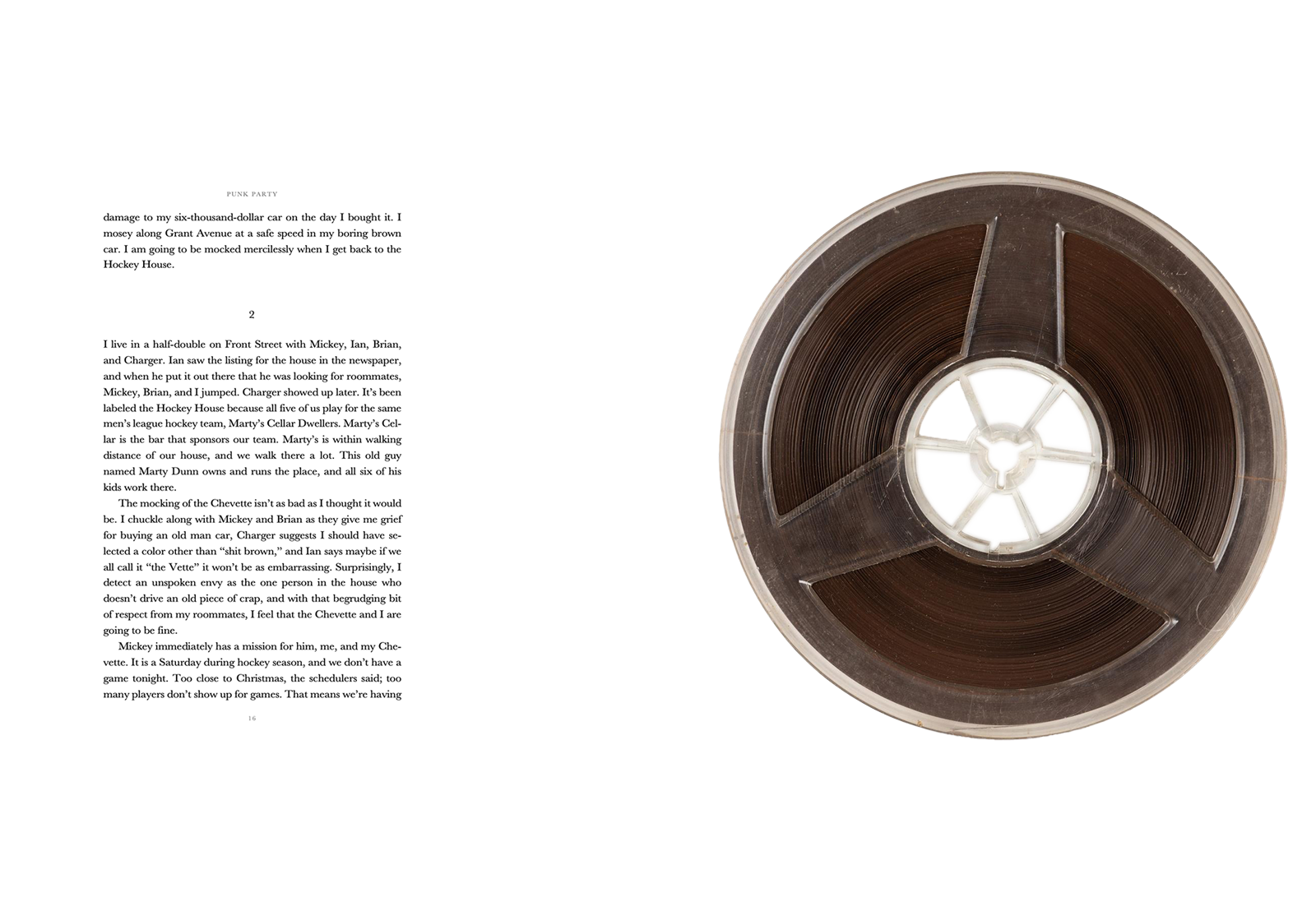

Art Jeinnings was not a draftsman. He, his wife Bonnie, and this weird guy named Charlie were Designers. They took our maps, and using a special Hewlett-Packard 97 Programmable Calculator, figured out what cable equipment would go where, and drew it on the maps. All of us—draftsmen and designers—were together in one room. Even with our large, six-foot by four-foot drafting tables, it was a cozy environment. Yeah, cozy. Let’s go with that.

I wanted to be a designer. First, I’d make more money, and second, I’d be able to use that special programmable calculator. It was almost … but not quite … a computer—and the thought of operating a device that came close to even resembling a computer was something I wanted to be part of. This wasn’t your ordinary, flimsy little calculator you’d take to tenth-grade algebra class. The Hewlett-Packard 97 had size and weight … a number pad with the heft of a typewriter … and all sorts of extra buttons called “function keys.”

And Art Jeinnings operated it like no one else.

His fingers flew over those keys like lightning—like a veteran cashier at the A&P; like a lifelong typist in the secretarial pool; like a concert pianist. He never looked at the keypad. He’d be hunched over the maps us lowley draftsmen had given him, eyes only inches away, the index finger of his left hand pointing to a footage span on the map while his right hand moved in precision—fingers like the wings of hummingbirds—entering coordinates on the keypad of the HP 97. After every number and function was input, the enter key would be struck with conviction and confidence, and the thermal printer would whir. Another calculation had been made, bringing more cable channels to the masses.

But designing cable TV systems wasn’t Art’s only special gift. Because all the while … as he worked tirelessly … bent over his desk …

Art talked to himself.

His day was a constant, personal recounting of his activities: “I’ll have to put a splitter on this pole.” “Not enough signal for an eight tap here.” “These are windey roads.” “Look at that, three 141-foot spans in a row.”

It is important to understand that Art was not talking to anyone in particular. He was there alongside everyone else, narrating his every thought; his every move: “What the matter with this ink?” “I can’t believe it’s already lunch time.” “I’m going to run out of thermal paper soon.” “There’s a glare coming right across my desk.” “My neck hurts.”

As you may have guessed, Art drove everyone crazy.

But the personal, verbal analysis of his day was only the beginning. Because mixed in to Art’s constant commentary on his life as a cable television designing savant, was his unfortunate mangling of the English language … specifically, as I said before, his uncommon virtuosity of the malaprop.

- Art wasn’t frustrated, he was flustrated.

- Sometimes he couldn’t extinguish one thing from the other.

- In the early morning, there was always compensation on the windows.

- He’d write things down because he wasn’t good at rememberizing.

I made it known in the halls of A.M. Cable that I wanted to be a designer, and Art took me under his wing. Soon he was my supervisor. Shortly after that, another company bought A.M. Cable and they downsized. Art and Bonnie were let go. (So was weird Charlie, thank god.)

Then we heard that Art was starting his own cable TV design company. Everyone at A.M Cable had a good laugh about that. How could a guy who said “gee wittakers,” or thought that the best course of action was to “bear and grin it,” or who owned a saw made by “Black & Dexter” run his own company?

I laughed along with everyone else until the word came that A.M Cable was shutting down for good, and we were all out of a job.

A month later I got a call from Art asking me if I wanted to work for him. He had more projects than he could handle, and it had changed his business plans drastically. (Or as he put it, “It threw a monkey wrench into the old ballpark.”)

I took the job. Art and Bonnie lived out in the sticks, and he had converted his basement into an office. Bonnie had a chicken coop out back. Art wasn’t lying. There was always work. He was always busy, getting things “coordilated,” often saying, “I’ll be working on this project a month from Sunday.”

And he was always bringing in new customers. I’d cringe when he’d be on the phone with these clients, mutilating the language; a cliché exploding machine: “Trunk Card.” “Smiling like a rose.” “Escape ghost.” “Statue of limitations.”

But it didn’t matter. Clients kept coming back to “Jennings Cable TV Corporation, Inc.” (Apparently, the incorporation thing was important to Art, hence using it twice in the company name.)

I keep telling myself that one day I’d like to write a story in which one of the characters speaks like Art, spouting out “How do you like those bananas?” or talking about his kid’s “pet rally” at school, or imploring someone to be “more pacific,” or to “quote me if I’m wrong,” or discovering he needed to “deleviate from his plans”—but it all seems too far-fetched … the character would not be believable.

But it’s all true. Each and every one of these:

- Dot-metric printer.

- Cry like a man. (I think you mean “baby.” )

- Irradical. (Irratic.)

- This conversation: “Bonnie, you’re making a mess.” “Mess?” “Yeah, you know, M-A-S-S, mess.”

- Or this comment while looking at the calendar: “Looks like Easter is on the 19th. Oh, it’s on a Sunday this year.”

- Or finding one of Bonnie’s chickens had died: “How do you put a price on a chicken?”

- Or this important advice: “Be careful when you assume, because you might make an ASS of U and I.”

Once, at a Christmas party, Art kept calling his special lime vodka punch “vine latka,” and when my wife Laura said she liked it, instead of jokingly calling her a lush, Art called her a slut. It was the only time, ever, that I saw a glimmer of realization creep into Art’s eyes that he may have said something wrong.

Art was an endless font of material:

- The coming of the Methias. (Messiah.)

- Martin Lutheran King.

- I throb on work.

- You gotta be serious!

- He called his new cordless mouse a “mouseless cord” for a month until Bonnie had had enough and corrected him.

- Condrums. (Condoms.)

- Deglect. (Neglect.)

- You hit it on the nutshell. (I guess that means something, I’m not sure what, though.)

And these, my personal favorites, that veer into the realm of sheer brilliance:

- I’m getting all emulsional.

- I detest there’s a conspiracy here.

And the ultimate … the tour de force … the masterwork:

Obstacle Delusion.

Art and I drifted apart long ago, like workers and bosses always do—but I loved the guy. We got along well, me and Art. I thought about Googling him as I wrote this, but thought better of it. I’m not typically a let’s-Google-somebody type of guy, and I think the David Beedle-Art Jeinnings relationship is one that should remain firmly rooted in the past.

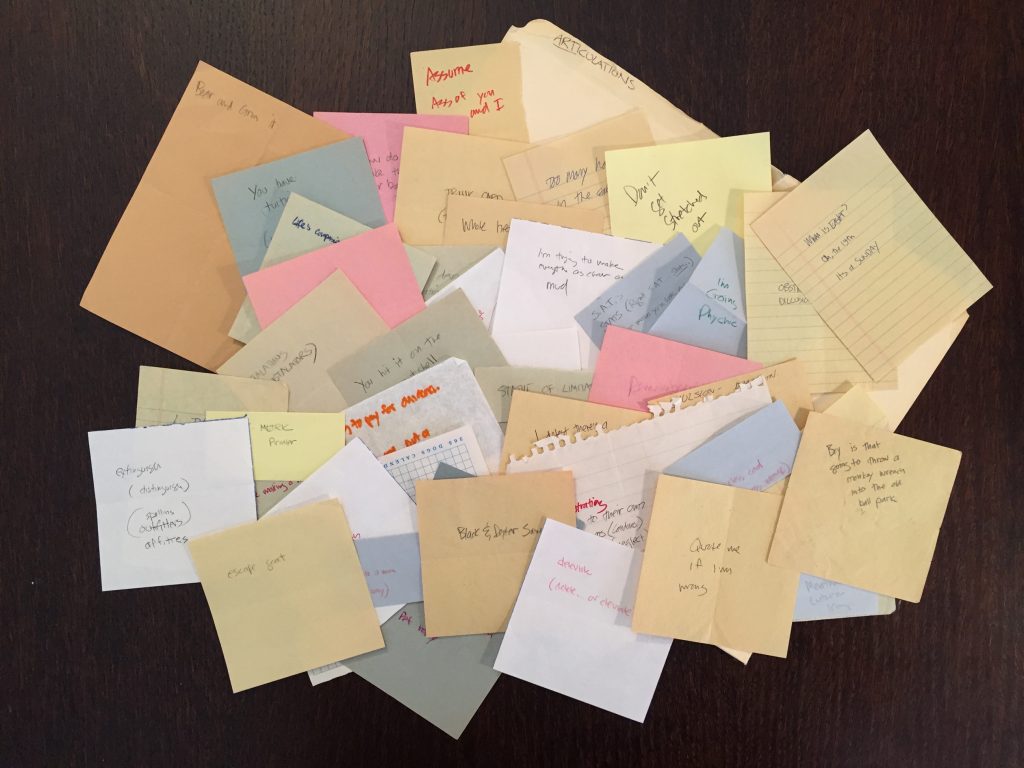

But I am forever grateful that for the years Art and I worked together, I would lunge for a notepad whenever he uttered another one of his timeless gems. I had to do it. I had to write it down, and slip that scrap of paper into my shirt pocket, and bring it home to be filed away in the Articulations folder.

Otherwise I would have forgotten. I’m not always good at rememberizing either.

Loved this I laughed out loud at least 4 times / sadly to say I have some of his same problems with language but thankfully my family usually understands or interprets 😉

This is the best yet!

Phenomenality . If you went ahead back any further ??? It would be like you almost just left.

Fantastic Writing DB.

David, I remember you bringing these gems up many times. I was always reminded of the late comedian Norm Crosby and his “command” of the English language. Unfortunately we live in a world that does not fully appreciate a person who is not solidly average. But it is these characters, those people who are slightly off center in some way, that make the world a vibrant and dynamic place.

I think of Art, and of you talking about Art, each time I hear a malapropism (hey Laura look that one up!). Art was somehow related to Terry Yeager, yes I am sure, since Terry was a huge fan of the guitarist Eric Clampton.

We need more people like Art in our lives. We live in an ultra-focused world were perfection is touted as the only route. This type of life lived is stifling and claustrophobic. I would never trade these unique people for a perfect world.

So here’s to Art Jennings, a man who has instilled in us the virtue that “when opportunity knocks you gotta pick up the phone”.

Hah!

Great

Eric Clampton

I loved those tiny pieces of paper filled with the verbal stylings of Art. His aim was true (even if his words might have missed the mark). Your story was a throwback to a simpler time. Art’s Christmas party and the vime lodka was a night to remember. Thank you for making me laugh, smile and feel young again!

You guys are the absolute best. Thanks!

Fantastic presentation David. I greatly enjoyed it and appreciate the fact that you had the presence of mind to write Art’s sayings down when uttered and then recount them for us these many years later.

So glad you enjoyed it, Don. Hope all is well in Seattle!